Third in a series on segregation and academic equity in MCPS. Check out part ONE | part TWO | part FOUR

UPDATE: This post was corrected to say that MCPS has named Watkins Mill High School, not Wheaton, an Innovation School.

Last week, we talked about how de facto segregation has made Montgomery County Public Schools a system of haves and have-nots, and at how watered-down attempts at integration made it worse. But for superintendent Dr. Joshua Starr, the real answer is making teachers better at teaching and students better at learning.

"I could come up with ways of mixing and matching kids from different backgrounds and different races and different stripes in schools," says Starr, "but unless you actually change what teachers do with kids every day, you're not going to get a different result."

I met Starr in his ground floor office at the Carver Center in Rockville, a former black high school that's now MCPS headquarters. 50 years after the end of official segregation, an "achievement gap" persists between black and Hispanic students and their white and Asian counterparts. Starr calls it a "moral and economic imperative." His official Twitter account says he's "committed to public ed for social justice."

Focus on teaching and learning, not on demographics

Before coming to Montgomery County in 2011, Starr was the schools superintendent for Stamford, Connecticut, which began busing students in the 1970's to encourage racial diversity in each school. However, it had little effect on academics.

"The tracking of kids was pernicious and incredibly problematic," he said, referring to the grouping of students by academic ability. Disadvantaged students were often placed in the lowest classes. "The education the black kids and poor kids and Latino kids got was horrific compared to what white kids got. While we integrated schools, the classrooms were not integrated."

Starr tried mixing kids of different races and backgrounds regardless of skill level and found that minority students performed much better. MCPS began trying this before Starr arrived with some success in some of the county's lower-income schools, but as he pushes for expanding it, some parents complain it holds high-achieving students back.

Another attempt at closing the gap is "project-based learning," which teaches students collaboration skills and critical thinking though exposure to real-life scenarios and new technology. The first school to try it is Wheaton High School, one of the system's poorest and lowest-ranked.

"There are kids that I saw when I was down there who were presenting their projects, 9th graders, 10th graders, that far exceeded what anybody in the county's done," Starr said. "When they graduate college, they will be highly sought-after as employees." Teachers at top-ranked Whitman High in Bethesda are studying Wheaton so they can bring the program there.

In May, Starr named Watkins Mill, Kennedy and Springbrook high schools "Innovation Schools," making them testing grounds for "new and innovative strategies" to improve student performance. They were selected along with 7 elementary, middle and alternative schools based on their low student performance rates and past attempts at improvement. They'll partner with the central office to design "school improvement strategies" for each campus, while principals would get extra coaching.

"We know that just by virtue of living near Walter Johnson High School, everything's going to be okay," Starr says, referring to a school in Bethesda. "Walter Johnson needs support too, and they're going to get it. But Springbrook needs a little bit more."

Integration the community's job, not the school's

Will better teaching be enough to fix the system's troubled schools? Starr can't integrate his classrooms if the schools aren't integrated to begin with, which he blames on the county's larger demographic trends.

"The students in the school are an outgrowth of the neighborhood ... it's just this natural progression," he says, noting that people have their own reasons for choosing private schools or moving to a certain neighborhood. While working in Stamford, Starr commuted from Park Slope, an affluent neighborhood in Brooklyn. Today, he lives with his wife and 3 kids in Bethesda, home to the school system's top-rated, but least-diverse schools.

After decades of trying to integrate its schools, MCPS needs outside help. "I don't decide housing policy. I don't decide transportation policy. We're a function of a community's decisions about how it wants to organize itself," he says. "My main job is 149,000 kids and their increasing diversity, and the needs that they have and what I need to do to get those kids what they need, wherever they're going to school and whoever they're sitting next to."

During his brief tenure, Starr hasn't shied away from controversial statements. He's called for a moratorium on standardized tests and expressed skepticism towards charter schools, even though the project-based learning program comes from one.

School reform advocates accuse of him of protecting the status quo, and MCPS officials suggest they weren't looking for massive changes. "We have a good thing going here, and we were not looking for candidates who were going to change direction," school board member Christopher Barclay told the Washington Post in 2011.

"Most people choose MCPS," Starr says. "The choice program we have [the Northeast and Downcounty consortia], it's working. Most people get their first choice and people are very satisfied with the choices they get."

It's great that Starr wants to give all students a great education regardless of background. But the isolation of poor and minority students in several schools, particularly in East County, suggests that many middle-class families aren't choosing them. That threatens both the system's future and the county's. MCPS can't fix it alone, but admitting that they have a problem would be a good first step.

"America has issues with race and it will always have issues with race," says Starr. "Montgomery County's a very progressive community. People are deeply committed to equity. There's a lot of evidence that in this county and this school system, people are able to live together."

"They don't seem to be able to go to school together," I reply.

"Issues of race have to be addressed if we are going to realize our full potential," Starr says. "That's in the school system as well. How you go about doing that becomes part of the challenge."

Tomorrow, we'll look at ways to meet that challenge in our final post.

UPDATE: This post was corrected to say that MCPS has named Watkins Mill High School, not Wheaton, an Innovation School.

Last week, we talked about how de facto segregation has made Montgomery County Public Schools a system of haves and have-nots, and at how watered-down attempts at integration made it worse. But for superintendent Dr. Joshua Starr, the real answer is making teachers better at teaching and students better at learning.

|

| Dr. Starr wants to make Wheaton High School a model of "project-based learning." |

"I could come up with ways of mixing and matching kids from different backgrounds and different races and different stripes in schools," says Starr, "but unless you actually change what teachers do with kids every day, you're not going to get a different result."

I met Starr in his ground floor office at the Carver Center in Rockville, a former black high school that's now MCPS headquarters. 50 years after the end of official segregation, an "achievement gap" persists between black and Hispanic students and their white and Asian counterparts. Starr calls it a "moral and economic imperative." His official Twitter account says he's "committed to public ed for social justice."

Focus on teaching and learning, not on demographics

Before coming to Montgomery County in 2011, Starr was the schools superintendent for Stamford, Connecticut, which began busing students in the 1970's to encourage racial diversity in each school. However, it had little effect on academics.

"The tracking of kids was pernicious and incredibly problematic," he said, referring to the grouping of students by academic ability. Disadvantaged students were often placed in the lowest classes. "The education the black kids and poor kids and Latino kids got was horrific compared to what white kids got. While we integrated schools, the classrooms were not integrated."

Starr tried mixing kids of different races and backgrounds regardless of skill level and found that minority students performed much better. MCPS began trying this before Starr arrived with some success in some of the county's lower-income schools, but as he pushes for expanding it, some parents complain it holds high-achieving students back.

Another attempt at closing the gap is "project-based learning," which teaches students collaboration skills and critical thinking though exposure to real-life scenarios and new technology. The first school to try it is Wheaton High School, one of the system's poorest and lowest-ranked.

"There are kids that I saw when I was down there who were presenting their projects, 9th graders, 10th graders, that far exceeded what anybody in the county's done," Starr said. "When they graduate college, they will be highly sought-after as employees." Teachers at top-ranked Whitman High in Bethesda are studying Wheaton so they can bring the program there.

In May, Starr named Watkins Mill, Kennedy and Springbrook high schools "Innovation Schools," making them testing grounds for "new and innovative strategies" to improve student performance. They were selected along with 7 elementary, middle and alternative schools based on their low student performance rates and past attempts at improvement. They'll partner with the central office to design "school improvement strategies" for each campus, while principals would get extra coaching.

"We know that just by virtue of living near Walter Johnson High School, everything's going to be okay," Starr says, referring to a school in Bethesda. "Walter Johnson needs support too, and they're going to get it. But Springbrook needs a little bit more."

Integration the community's job, not the school's

Will better teaching be enough to fix the system's troubled schools? Starr can't integrate his classrooms if the schools aren't integrated to begin with, which he blames on the county's larger demographic trends.

"The students in the school are an outgrowth of the neighborhood ... it's just this natural progression," he says, noting that people have their own reasons for choosing private schools or moving to a certain neighborhood. While working in Stamford, Starr commuted from Park Slope, an affluent neighborhood in Brooklyn. Today, he lives with his wife and 3 kids in Bethesda, home to the school system's top-rated, but least-diverse schools.

After decades of trying to integrate its schools, MCPS needs outside help. "I don't decide housing policy. I don't decide transportation policy. We're a function of a community's decisions about how it wants to organize itself," he says. "My main job is 149,000 kids and their increasing diversity, and the needs that they have and what I need to do to get those kids what they need, wherever they're going to school and whoever they're sitting next to."

During his brief tenure, Starr hasn't shied away from controversial statements. He's called for a moratorium on standardized tests and expressed skepticism towards charter schools, even though the project-based learning program comes from one.

School reform advocates accuse of him of protecting the status quo, and MCPS officials suggest they weren't looking for massive changes. "We have a good thing going here, and we were not looking for candidates who were going to change direction," school board member Christopher Barclay told the Washington Post in 2011.

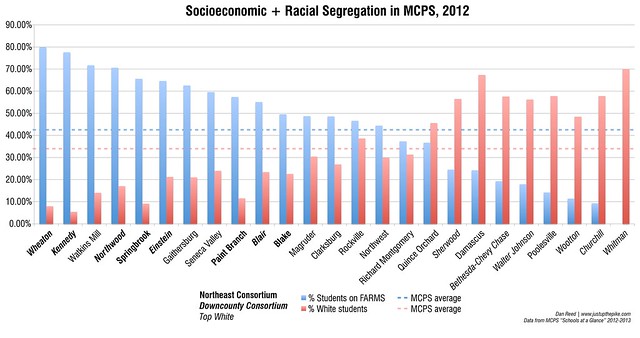

"Most people choose MCPS," Starr says. "The choice program we have [the Northeast and Downcounty consortia], it's working. Most people get their first choice and people are very satisfied with the choices they get."

|

| Students on reduced lunch (in blue) and white students (in red) are each concentrated in a few MCPS schools. |

It's great that Starr wants to give all students a great education regardless of background. But the isolation of poor and minority students in several schools, particularly in East County, suggests that many middle-class families aren't choosing them. That threatens both the system's future and the county's. MCPS can't fix it alone, but admitting that they have a problem would be a good first step.

"America has issues with race and it will always have issues with race," says Starr. "Montgomery County's a very progressive community. People are deeply committed to equity. There's a lot of evidence that in this county and this school system, people are able to live together."

"They don't seem to be able to go to school together," I reply.

"Issues of race have to be addressed if we are going to realize our full potential," Starr says. "That's in the school system as well. How you go about doing that becomes part of the challenge."

Tomorrow, we'll look at ways to meet that challenge in our final post.

3 comments:

Starr says, in-part: "The students in the school are an outgrowth of the neighborhood ... it's just this natural progression [...]"

But that was the whole point of busing as it was court-ordered in the 1960s-1970s and possible even later on.

The courts found that segregated schools in segregated neighborhoods were in fact not "separate but equal"; rather, they were merely separate and unequal and both perpetuated long-standing historic inequities and tended to prevent education from imparting any capacity in upwards mobility, to get out of the neighborhoods perpetuating inequity.

Dan, you are commended for having the courage to point out the facts. Yet don't expect any love from Starr or for that matter from the people who put him in place and who probably have told him that his job and future employability depend on him spouting the party line.

Montgomery schools are, right now, the biggest and increasingly the only remaining selling-point. It's what makes the place desirable and attractive to the highly educated workers who are the mainstay of the County's only real remaining engine of industry, the medical/medical-industrial and research sector. Tell the PhDs that their kids will get a second-rate education and they assuredly won't take a job here, no geniuses equals no progress in these industries, and that means they go elsewhere. And so does the tax base giving power to our politicians.

We increasingly see the County sloshing a whitewash over real problems and they seem to have the notion that if you ignore bad news, it will go away. I will go away, for certain, but that's not going to make County schools less segregated. Nor will it make them better, segregated or not.

This issue is like the whitewash they tried to slosh around on the gang problem. They were telling people who just had every sign and sidewalk "tagged" in their neighborhood, that "categorically speaking there are no gangs in Montgomery County". The proof of the lie was already visible yet the officials prevaricated to keep their jobs while looking for guidance to officials who couldn't be honest enough with themselves to admit that they could be wrong, that there could be a problem. Or else, most likely, they were just fresh out of ideas.

Busing, while an old idea, will work.

Honestly? I think the Barclay quote tells us everything we've ever needed to know here. After the remarkably (and sometimes unnecessarily) controversial Weast years, the BoE and, to some extent, the population, wanted someone safe as milk. That's what we got--leaving parents free to continue to insist that their special snowflakes be in theoretically more challenging classes than the dirty, dull snowflakes.

And mind you, while I'm truly perfectly okay with my general-population special snowflake getting gray and tarnished (our other snowflake is truly special, and outside of the mainstream), I still allowed him to choose a magnet school that, by your chart, is one of the five whitest schools in the county ("white" being an interesting term of art in MCPS-speak, but it's close enough). So it's not like I think I deserve to be taken all that seriously on this issue.

Here's an email I got from one commenter:

"But for superintendent Dr. Joshua Starr, the real answer is making teachers better at teaching and students better at learning."

So the problem is the teachers. Right.

I teach at one of the "W" schools. I'm convinced that there's zero difference between a teacher at my school over a teacher at any other school in terms of dedication and overall professionalism. That said, a teacher at one of the lower achieving schools is apt to want to get out of where they're at to some to a "W" school because they're sick of the problems they encounter at the other school.

The problem is that kids at the non-W schools are no where near as supported, guided, and watched over by their parents as in the typical "W" school. Black/Hispanic families have lower education at the parental level, lower understanding of the system itself, and are far less involved in the system as the "W" school parents, and this translates into a kid who's often out there on their own, subject to the whims and dangers of their environment and peers. This results in a student less inclined to think that what they're there for is important, more inclined to be a problem, and less apt to have the tools that allow them to step into an academic environment to be successful.

Yes, a quick fix is "improve" the teachers. Yeah, right. You're doing something, you can brag about it, but it's all smoke and mirrors.

This is a societal problem requiring FAR more support and involvement from the county, or MCPS, and requiring a degree of societal involvement that likely would neither be popular or welcome. We’ve all been perpetuating a failure that's been endemic everywhere for as long as there's been notice of the problem.

Bottom line, it's not the teachers, it's FAR more than that, but to do what would really need to be done would be far more controversial, entail far more pain than anyone would care to take on, and take too long to really show results. Maybe charter schools are the answer, something radical and outside the current system, which takes on most if not all of the challenges I mention here and has a measure of success that right now we aren't seeing in Kennedy, Wheaton, et al.

Post a Comment