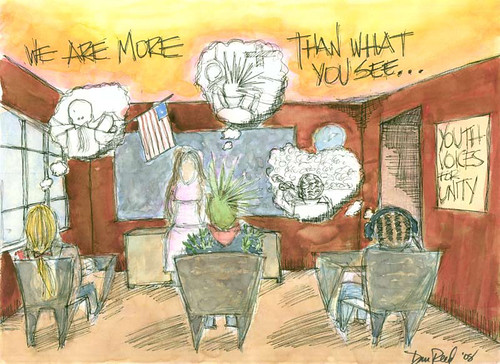

My poster for Youth Voices for Unity.

My poster for Youth Voices for Unity.Wednesday was my last day of studio, the culmination of two years of hard work and growth and my first chance in a week to sleep for more than four hours. Now, I have to think about what I'm going to do after college - not surprisingly, it's been difficult to even land an interview at architecture firms in the area. For most of the past year I've been wondering what I could do to work with young people - advocacy, organizing, maybe even design work, you know, help to create places that are as important to local teens as "the Turf" was.

I've thought about substitute teaching as well. As frustrating as it will be to move back home after my lease in College Park runs out this summer, I joke that going back to teach classes at my old high school will complete the fantasy that I've returned to 2005. Four years can make a difference, and between changing demographics and fears that the Northeast Consortium may have been a failure, returning to Eubie High could result in some serious culture shock.

"Blake is so ghetto now," says a girl in my a cappella group over dinner last weekend. She graduated two years after me, and has cousins who goes there now. "No, it's not," I reply. She gives me a look like I just said the sky was green, and I add, "as long as Blake serves Stonegate and Hampshire Greens, it'll never be ghetto." Meanwhile, our friend who grew up in D.C.'s trying to figure out how any place in wealthy Montgomery County can be "ghetto" or even just "not rich," which just makes the explanation even more convoluted.

I just came back from an evening in Alexandria with the kids and teachers of Youth Voices for Unity, a group that's all about dismantling stereotypes and prejudice. Stereotypes like a school with any amount of poor or minority kids (which, in the case of Blake and White Oak, is more than there were when I attended them) is going to be "ghetto" or "violent." Last fall, I sat down with students from T.C. Williams High School (you know, where Remember the Titans was set) and created a poster that was finally unveiled tonight, and will start to appear around Alexandria soon. These kids were white, black, Latino, rich, poor, whatever - and they told me about basically growing up typecast as future failures.

And here in East County, the story isn't much different. A headline in today's Examiner screams "Violence a daily fact of life in area schools," citing that the most suspensions in MoCo are handed out to students at Key Middle School and White Oak (where I went to middle school) - and, of course, that two kids at Springbrook High tried to bomb their school last week.

All of East County's schools have larger populations of minority and low-income students now - and the "problems" associated with those populations - so much so that civic activist Stuart Rochester regularly mentions the issue of "student transience" in discussing any proposed local development. (And it was enough to convince the Planning Board to approve a waiver this afternoon for required MPDUs in the Fairland Park project in Burtonsville.)

I don't want to sound all wimpy and say "these words are hurtful," but no matter how hard I'd want to have my street cred, I wouldn't tell anyone I grew up in the ghetto. What kind of expectations would that set up for me/my family/who I grew up with/this place that I called home? Issues like school violence and student transience are important and demand our attention, but what kind of expectations do we set up for ourselves when we blow that up into an indictment of our community?

Architects work to create "places." I want to talk about making "place," but before I get out the bricks and mortar, I think it's time to start building with words.

2 comments:

Ghetto is a state of mind as much as an economic condition. Public acceptance and tolerance of cultural degeneration is as much of a problem as poverty. It is a question of personal dignity. There are certain values such as personal responsibility, honesty, intellectual advancement, and healthy ambition that need to be more overtly embraced by society and it's institutions. Unfortunately, as long as the contemporary culture consumed by todays youth places equal or greater emphasis on " street creds " and fashion as it does on

positive, productive, personal development, we will continue to decline as a society.

I love the poster, and I really like the direction you're taking in your life. If we're going to have real change, we need more people who are willing and able to engage young people, and help them sort through this mess us old folks have made.

It seems like many people tend to view today's kids as being highly privileged, and focus on the fact that they have so much more than kids before them. Sure, some kids do have a lot. But there's plenty who don't, and whether or not kids have money and resources in their lives, they all have more confusion than my generation had to deal with, and many more complex issues. And in general, I don't think adults are cognizant enough of that fact, and of how stressful life can be for kids these days.

Kids need all the advocates they can get. I'm really happy to hear you're going to be working with youth and on youth issues.

Post a Comment